Our First Year with Solar Panels

DISCLAIMER: This blog post was updated on November 4, 2018 with corrected energy data. I recently discovered I had been reading my electricity bill incorrectly* and had to revise my calculations — the following reflects updated numbers and charts.

We got solar panels installed on our home on 22 April 2016 — Earth Day, coincidentally. We now have a full year's worth of energy data since they were installed, so I thought I would look at how much energy they produced and how much we consumed during our first year of having solar. Fair warning: this post will inevitably be pretty wonky. I'm glad to delve into technical details further in comments or elsewhere if people are interested, but for the post itself, I've tried to keep the wonk in check.

One of the primary goals of our home renovation project is to reduce our environmental impact by reducing the carbon emissions associated with operating the house. In addition to reducing our energy consumption through robust efficiency measures, we decided that it also makes sense to generate our own renewable energy on-site to power the house. Since we're in the Pasadena, CA area, — with 286 sunny days per year — rooftop solar panels made sense for on-site renewable generation.

Usually it makes more sense to reduce consumption through efficiency measures (and conservation) before adding on-site renewables. Saving a kilowatt-hour (kWh) of energy through efficiency is often cheaper than generating that same kWh through a solar electric photovoltaic (PV) array. However, at some point after the "low-hanging fruit" efficiency measures have been completed, the price of reducing a kWh through efficiency matches the price of generating a kWh with a PV array, and at that point, it makes more financial sense to switch from reducing energy demand (efficiency) to changing the source of your energy supply (renewables). This break-even point is changing as the price of solar panels falls lower and lower.

A local solar company putting supports for PV panels on our roof. No that's not a tiny man on the ladder.

In our case we knew from the beginning that we wanted a PV array, but we didn't want to wait until after the renovation was complete before installing it. We wanted to switch to renewably-generated energy as soon as possible, so we had the array installed before even beginning the renovation. This meant we had to size the array before knowing exactly how much energy our house would use. We intentionally oversized the array, allowing for excess generating capacity to power potential electric vehicles and to cover the energy consumption of a more typically-behaved household in the event that we sell the house later.

This is Carlos, who runs the company that installed our panels. He's a badass.

As part of the PV installation, our old Zinsco electrical service panel got replaced with a new 200-amp one.

Here's what the new inverter and service panel look like after installation.

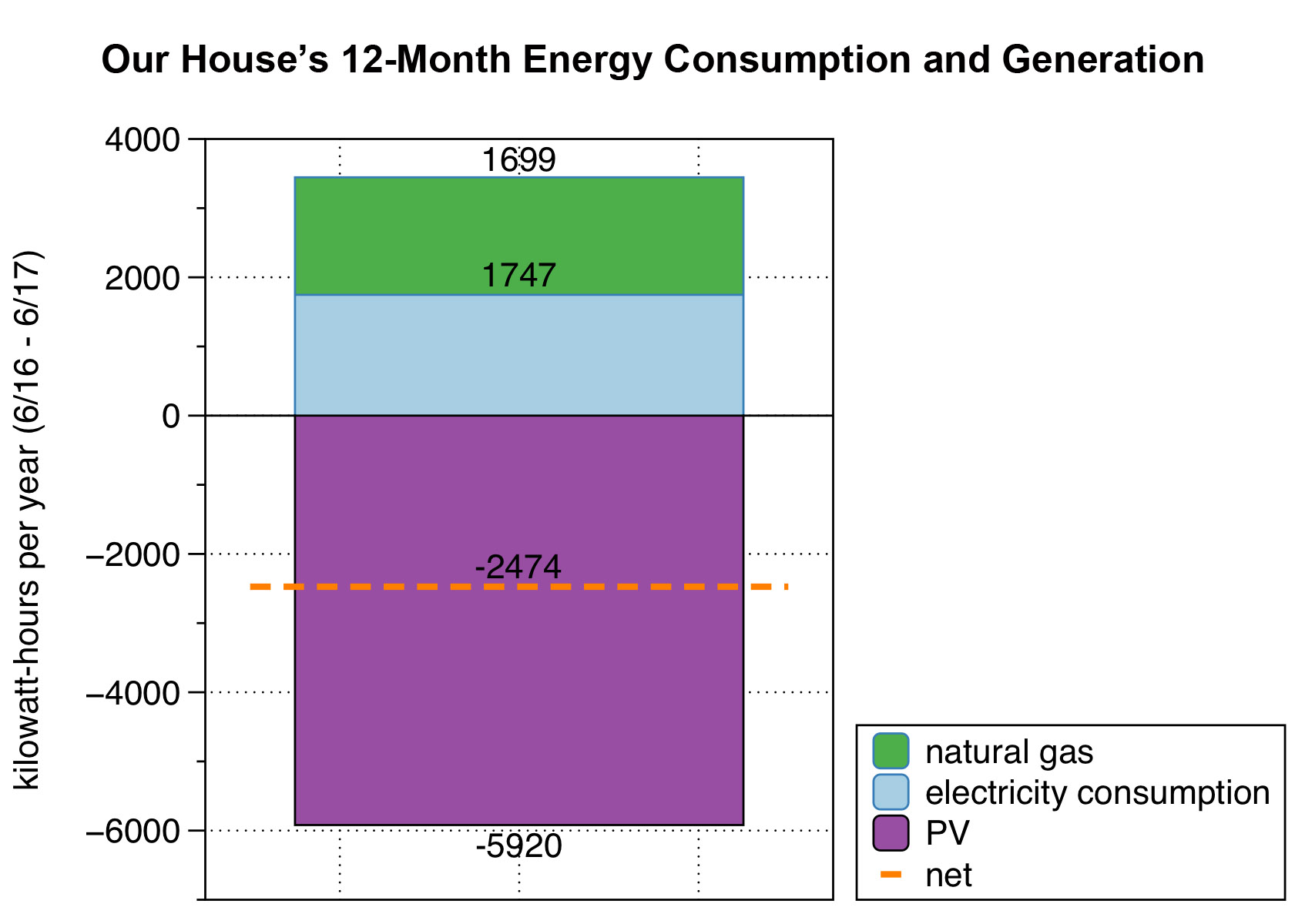

We had a 4-kilowatt (kW) array installed in April 2016. It went online in May 2016. It was a magic moment when got the go-ahead from our utility and switched the inverter on, and saw the digital readout telling us that we were sending power back to the grid because we were generating more electricity than we were using. From June 2016 until June 2017, our house (and its occupants) consumed 1747 kWh of electricity. During the same period, our PV array generated 5920 kWh, 339% of what we consumed.

But of course, electricity is usually not the only form of energy that a home consumes. In our case, we also consume natural gas, because we currently use it to heat our water. During the same period, we used 58 therms — or 1699 kWh — of natural gas. This brings our total household 12-month energy consumption to 3446 kWh. The 5920 kWh of generation represents 172% of our total consumption; we generated over 1.5 times as much as we consumed. There are more thorough and complex performance metrics that can be used (site vs. source energy, kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent averted, adding water consumption, etc.), but for now, this is good enough.

We generated more energy than we consumed for ten out of the twelve months, with January and February being the exceptions (not surprising, as these are the months with the least amount of sunshine).

These days, homes that generate as much energy as they consume — so-called "Zero Net Energy" (ZNE) homes — are all the rage. And not without reason. It's great to be able to tell people you live in a ZNE home, even if there's inevitably a tinge of smugness and superiority entailed in doing so. Another approach that's functionally equivalent, but not as easily bragged about, is to purchase grid-delivered electricity that is generated at a large-scale PV or wind-turbine facility far away. This is a good option for the large number of households for whom on-site generation doesn't make sense, and in fact it's likely more efficient (and cheaper) than on-site PV because it makes better use of economies of scale. However, from my perspective, interacting daily with the equipment and forces that generate the energy that you use makes all the difference. It removes some of the abstraction of the grid and the unseen far-off place, and makes energy — an inherently abstract entity — a little more relatable.

In time, I think ZNE homes will just be referred to as "homes" — meaning that every, or nearly every, home will eventually become ZNE. California is already on this path. By 2020 all new homes built in California are required to be ZNE. The formulas that the state uses to evaluate whether or not a home is ZNE, as well as individual household behavior, will mean that every home built after 2020 will not necessarily generate as much energy as it consumes. But on aggregate, they should be close enough to net-zero that their overall impact on the electric grid will be negligible.

I am curious to see how our home's generation vs. consumption changes as the renovation gets closer to completion. Our first 12-month period of having solar is a little unusual because our house is a construction zone. We're running power tools for hours on end, but we also don't have any central heating or cooling system (we use a space heater and portable air conditioner), but also we don't have an oven, but also the house is not well insulated...all that to say, there are a lot of balls in the air right now, so it's hard to guess whether our overall consumption will be significantly different once the renovation is complete.

We're replacing the gas water heater with a heat pump model that should use significantly less energy, but we're also adding a whole house space conditioning system, new kitchen appliances, etc. Who knows which way it will all wash out. I suspect that after everything is done we'll use about as much energy as we do now, or slightly less, but we'll be much more comfortable and have a lot more services.

The more important thing is that after the renovation, whoever lives in this house will likely use a lot less energy than they would living in a typical house. Frankly, it doesn't really matter that much where we live — we will always be low energy users. It's just the way we are. The real energy savings and carbon reduction potential comes from the (normal) people who don't think about energy or climate constantly — they are the people who use the energy and whose reduced consumption will make a big difference.

* Turns out I had been reading my electricity bill incorrectly — I presumed the consumption and generation numbers on the bill were gross amounts, but discovered recently that these numbers represent the cumulative net amounts (e.g. If the bill says we used 76 kWh of electricity in a month, this number includes the amount offset by the solar panels, so our consumption was actually higher than 76kWh). Likewise, when we were exporting energy, the exported number on the bill has already had the consumption subtracted from it. In short, the utility bill is good for keeping track of how much money we owe for energy and how much they owe us, but incredibly there’s apparently no way to determine from the bill how much total energy we’ve consumed and generated. To retroactively determine the actual consumption and generation, I found a way to download the raw generation data from our PV meter and used these with the bill figures to calculate our actual consumption and generation data (seriously, why is this so hard?). I’m embarrassed to report that we had overstated our conservation badassery in the first version of this post (our energy use is low, but not as insanely low as previously reported). I’m also happy to announce that our solar panels generate more than we previously thought (and more in line with their predicted generation). In the end the net consumption number is about the same. In the spirit of accuracy and integrity, I wanted to make sure to update this post with the revised numbers and charts. Apologies for the confusion and thanks for putting up with science in motion. We’re all still learning.