How We Turned Our House into a Giant Foam Box, Part I — Wall Insulation

It turns out that one of the most important determinants of how much energy your home uses is also one of the most invisible: Insulation.

I know, insulation is soooo unsexy. No one ever sees it or thinks about it.

But imagine being outside on a very hot summer day. Would you rather take shelter inside a box made of wood or Styrofoam? Same question on a freezing, snowy winter day. In both cases, of course you'd choose the foam box. Insulation makes a difference!

Thermal insulation is basically any material that heat can't travel through easily (like foam). When a building is protected with insulation, it helps keep the inside temperature the same, even if the outside temperature changes. The more insulation a building has, the more stable the indoor temperature (and the less energy is needed for heating and cooling).

So that's why we decided to insulate the s*** out of our house. In other words, turn the house into a giant foam box.

Oh, look! Here's the foam now.

To be honest, this is hard, tedious work to do on your own. It took Chris 3 months to insulate just the walls of our common rooms (part I, what your reading now). The ceiling took another 4 months (what we'll cover in part II). It turned out to be bigger and more overwhelming than we could have imagined. But to us, it was worth it.

For the past 35 years, our house had only a thin layer of insulation in the attic and absolutely zero insulation in the walls or floor. Which meant that in the winter whenever we turned on the heater, nothing would keep the heat in so it would quickly escape out the building, and the furnace would have to keep running hard for the house to stay warm. The opposite would happen in the summer with the air conditioner. In other words, we were wasting huge amounts of energy. Not good.

Our solution? Cover all the exterior surfaces of the house with high-quality insulation. For our region, California code requires new homes to have an insulation value of at least R19 in the walls and R38 in the ceiling. Since Chris is so passionate about this, he decided to make our walls R26 and our ceiling R46. Take that, climate change!

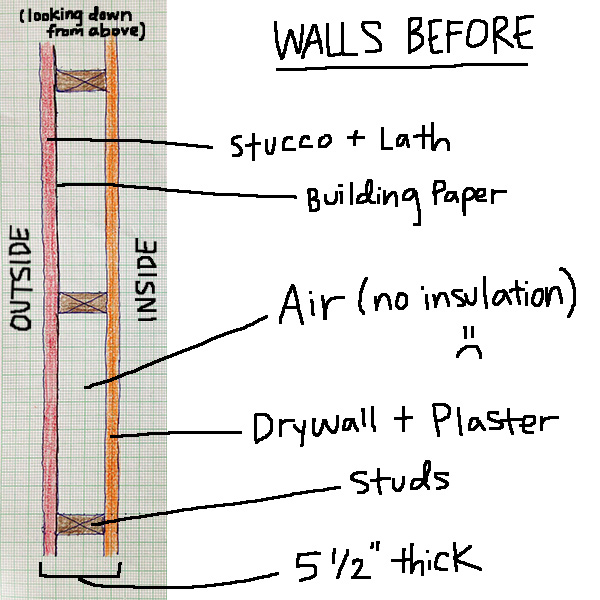

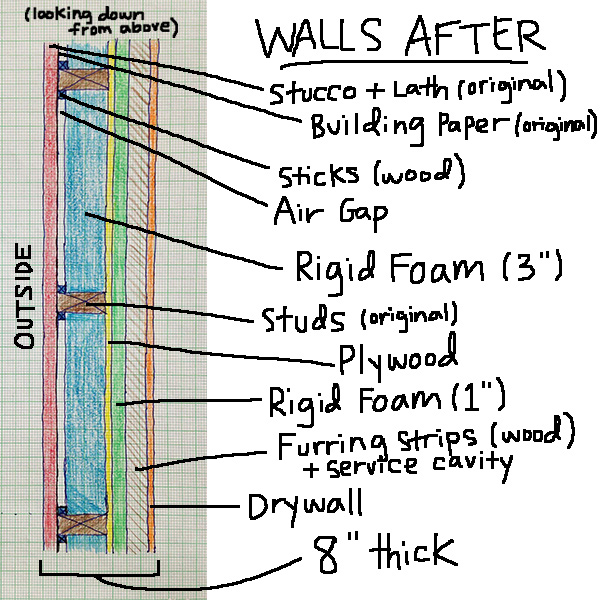

Chris did a lot of research (reading online and consulting professionals) to figure out how exactly to insulate the walls. Below are diagrams illustrating our original wall assembly vs. Chris' new design. Accurate, to-scale sketches by Chris; child-like penmanship by me.

As you can see, the new assembly is rather beefy and intricate! The wall thickness increases from 5.5 inches to 8 inches (yes, our rooms will actually be a tad smaller after all this is done). While it is quite intimidating to construct something so complex, Chris took it one layer at a time.

Phase 1: Rigid foam (3 inches)

Before putting in any insulation, Chris cut thin long "sticks" (1/2" x 1/2" wood) and stuck them in the back corners of each empty bay. This created a small air gap, just in case any moisture (like rain) somehow manages to get into the wall assembly in the future. Pretty unlikely in our dry climate, but it's important to allow moisture to dry out so there's no risk of mold or rot in the walls. My cousin Hank and our friend Ernie helped with this process — thanks guys!

Now, we were ready for the foam.

So... we needed a lot of foam. Over 100 sheets, actually. #thestackistallerthanme #morningdeliverymeanspjpants

This type of insulation is called rigid foam insulation. The technical name of the material is polyisocyanurate (say that three times fast!), or polyiso for short. There are other kinds of insulation that are more commonly used — such as fiberglass and cellulose — but rigid foam is much more effective (and, uh, expensive).

Here is what our walls originally looked after we removed the drywall. Empty bays. Chris' goal was to fill each bay with a 3-inch layer of rigid foam.

The upside to rigid foam is that it's one of the best insulators available. The downside is that, well, it's rigid. While cellulose or fiberglass insulation is squishy and easy to stuff into different shaped spaces, rigid foam doesn't have that flexibility. It has to be cut to fit.

Which meant Chris had to carefully measure the dimensions of every bay (which were all just very slightly different), and cut a custom piece of rigid foam into the exact size and shape of each one.

That sounds fun, right? Good thing Chris' strongest personality traits include stubbornness and perseverance. :)

Chris used a table saw to cut each 4' x 8' foam sheet into smaller pieces. He wore a respirator because cutting the foam filled the air with a cloud of fine polyiso dust. It's kind of like snow, except it never melts and will probably make you sick if you breathe too much into your lungs. #safetyfirst

After using the table saw, Chris manually cut the foam to precisely fit each bay. For this he used a circular saw or a Japanese Kataba saw.

Then he would install each cut piece into its corresponding bay, by gently pounding it in place with a mini sledge hammer and a block of wood.

Because we vaulted our ceiling, often Chris had to make diagonal cuts at exact angles, which was a pain to get just right.

It was a slow, painstaking process. Chris completed 5-10 bays each day. Slowly but surely, the walls started filling up with shiny foil-faced foam.

Finished the largest wall! Celebratory jump:

Kitchen wall before and after:

After several weeks, Chris finally finished all the bays, woohoo! But wait, there's more. Time to AIR SEAL.

I didn't know this before, but Chris explained to me that air sealing is a critical, often overlooked step when insulating a building. Without air sealing, you just end up with a foam box full of holes and cracks. So Chris used caulk or canned spray foam to seal every seam around each bay. Tedious, but important!

Insulated and air sealed!

Phase 2: Plywood

The next step was to cover the walls with a layer of plywood. This actually had nothing to do with insulation, but instead was about earthquakes.

Our house was constructed in 1963 and had very little seismic supports built in, which is scary since California is riddled with fault lines. Adding a layer of plywood over the building frame helps provide lateral (sideways) support and keep our house from collapsing during a big earthquake.

Thankfully, Chris' big brother Charlie visited from Cincinnati and stayed with us for a month, and was a HUGE help with the house project. Thank you, Charlie! You're the best. :)

With Chris and Charlie combining forces, construction moved ahead at a faster clip. Enjoy these photos of our walls transforming from silver foil to brown wood:

P.S. I love that the Chinese good luck red paper thingy stays up on the door throughout the entire construction process. We'll take all the luck we can get!

Phase 3: Rigid foam (1 inch)

Now that we have impressive plywood walls, what's next? Why, another layer of rigid foam, of course!

You might be wondering why on Earth we're adding more rigid foam. Didn't we already do this? Yes, mostly. But remember that Chris only put the rigid foam inside the bays. Which means that the framing around each bay actually did not get insulated. Let's revisit my favorite photo:

As you can see, all the wood studs and blocking are uninsulated, so that heat can still "leak" in and out from those places (this is called thermal bridging). It's like we have a beautiful thick wall of rigid foam, but it's full of cracks.

To address this, Chris and Charlie added yet another layer of rigid foam on top of the plywood, except this time only 1 inch thick and continuously covering the entire wall.

And yes, they air sealed this layer of rigid foam too. Now there will definitely be no leaks! The most airtight giant foam box house evarrrrr.

Phase 4: Furring strips & service cavity

Insulation is now complete — hooray! But wait, there's more (again).

We can't put drywall (the final, finished layer) directly onto the rigid foam, because we need some space behind the drywall (a service cavity) to put things like electrical wiring and HVAC tubing. Chris' solution was to install horizontal strips of wood, called furring strips, over the rigid foam.

The furring strips create a service cavity where we can run wiring and such behind the drywall. They will also serve as anchor points for electrical outlets that will be installed later on.

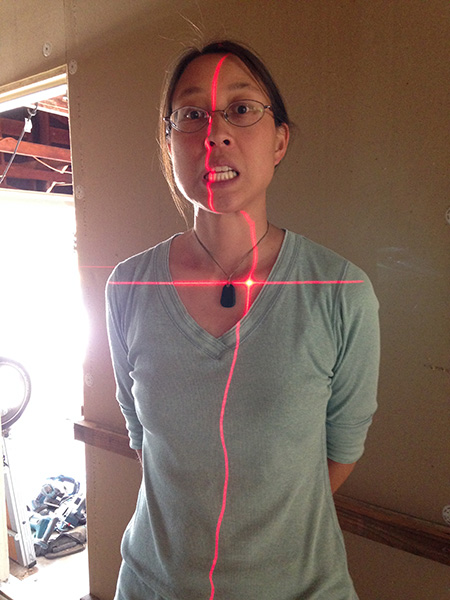

Chris and Charlie used a laser level to make sure the furring strips were perfectly horizontal and parallel...

...and I used the laser level for expressive body art.

Here are our lovely insulated walls, with furring strips and service cavity in place!

Fully insulated with 4 inches of polyiso rigid foam, seismically supported with plywood, and air sealed not once but twice — our walls have never looked so good! Ready for wiring, and then the final drywall.

It's just a shame that all this awesomeness will be hidden inside the wall for no one to see. The only proof that Chris spent 3 months painstakingly insulating the walls are, well, these photos. That's how it goes with insulation. #unsunghero

The proud Stratton brothers stand before their towering work.

Great work, guys. But the fun's not over yet. Next up, adventures in ceiling insulation! Click below for Part II and read all about it.

READ MORE: